By MC Catanese

Reality Toward Light in

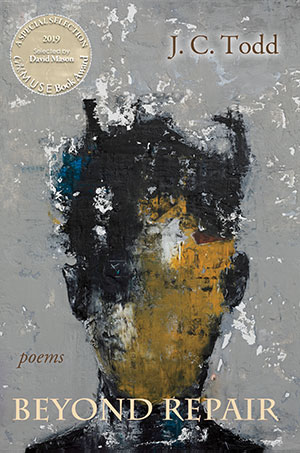

J. C. Todd’s Beyond Repair

Poet J. C. Todd’s latest book, Beyond Repair is an evocative collection of poetry examining the effects of war, explored through the poet’s compassionate lens as a civilian writer and observer. The past and the personal are blended in a pastiche that bears witness to the intensity of armed conflict and the poignant realities of the wars fought during the poet’s life from 1943 until the collection’s recent publication—a span of seventy-five years. The book focuses on centers of military conflict in the Middle East, Asia, and Europe. These external landscapes resonate with the internal geographies of the speakers in Todd’s poems. Sometimes the language is raw and direct and other times the reader is invited to melt into her more subtle, achingly felt, lyricism.

In Todd’s collection, inner growth happens in tandem with the violence occurring in the outer world. For example, the prologue poem, “In Whom the Dying Does Not End,” features a pregnant speaker. As she contemplates the internal embryonic blossoming of her daughter, “Just as her eggs begin / to cluster along the genital ridge,” another development unfolds, far away in Syria in the city of Hama. President Hafez al-Assad, father of current Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, unleashes a bloody assault “to crush the revolt of / the Muslim Brotherhood,” where al-Assad’s own people are massacred: “Twenty thousand dead– / some say more—in twenty / days,” while within the body of the speaker, there are similar numbers of conversely life-affirming fetal developments, as the speaker tells us her daughter’s “thousand, / thousand, thousand cells / swelled and halved dividing / into human….” The intersection of inward consciousness and awareness of brutal external realities, then, casts the slaying of “Thousands distilled / into smudge, smear, stain” into a context where one can feel the atrocity more powerfully; the space between the development of new life and the destruction of existing life begins to feel closer than one might have otherwise imagined.

Although the subject matter of the effects of war is weighty, there is a countervailing force within each carefully chosen word and crafted line that creates a feeling of hope.

Because of Todd’s expert poetic craft and engagement with multiple poetic forms, the reader’s imagination is activated in diverse ways. For example, “The Girl in the Square” is an ekphrastic response to a video filmed in Cairo during a period of civil unrest known as Arab Spring. The poem references “Tahrir Square,” where “the boots that are sure to come” suggest a scenario of soldiers trying to quell the political demonstrations in Egypt in December, 2011. The poem features a series of couplets which begin by announcing what the sky portends, “that tint of what’s to come,” and gradually turn to the body of a girl kicked by the soldier’s boots, “washed out, amnesic” in the aftermath of the violence. The journalistic report of the video is transformed by the lyric sensitivity of the poet. Perhaps it could be said that in the film of the body “shot anonymously” the viewer sees; but in the poem, the reader sees more—an interplay between the news report that “holds her up to memory,” and the profound sense of loss that readers are free to amplify within their imaginations, via the metaphor of “the torrent” which “swept her away.”

What is compelling about the ten sonnets that form Todd’s second section about a triage doctor’s experience serving in Iraq can be seen in the poems’ relationships to each other. In this poetic tour de force, repetitions between the poems (utilizing the form of a crown of sonnets) serve to connect them. Repeated lines are followed by a sense of new insight, a different element in each subsequent poem that brings heartbreaking clarity and dimension to the sense of all of it being “fucked up by damage beyond her [the triage doctor’s] control.” The crown of sonnets is a paradoxical joy for the reader to experience even within the brutality of their content. Within this group of poems, bearing witness to human desecration, “…Where the arm was, the medic strokes air,” and its wretched physical and psychological consequences, the life-affirming power of language is orchestrated to help reinstate what war obliterates. Through poetic process, one can feel a certain positive energy, i.e., that it just may be possible for the trajectories of bombs to ultimately give way to new trajectories of thought. Although the subject matter of the effects of war is weighty, there is a countervailing force within each carefully chosen word and crafted line that creates a feeling of hope.

The next section of Todd’s book focuses on post-traumatic stress among women who serve—a group generally not represented in discussions of military PTSD. Through specific scenarios, Todd aligns the reader with the effects of intense trauma, and by playing with the double meanings of words, the poet unites what is easy to understand with the lesser-known harshness of war zone trauma. In “Under the Weather,” for example, “the sky’s underbelly drooping, / spewing blips and funnels,” one sees the double meanings: “blips” of weather signaling possible tornado “funnels” on a radar screen can also be read as “blips” in the sense of mass graves of people turned into dust and ‘funnels’ are also craters created by bombs. Similarly, “…raining cats and dogs…” of the traditional idiom becomes what really is under siege: “…it’s frogs and I-beams, picket fences,” or “the topsy-turvy village flying up.” A dance with the known opens the doors to empathetic consciousness about unknown horrors.

J. C. Todd choreographs the complexity of the ordinary in her fourth section about wars on foreign soil and ongoing fears she and many women experienced at home. In “Imagining Peace, August 1945,” the setting is a family picnic at “war’s end,” where “After the A-bombs, the assembled rejoice with “icy / Rheingold and just-raked steamers whose shells tilt up / like an empire of faces raised toward /a hiss from sky…” Of course, Rheingold was a very popular beer post WW II, but sonically, one also hears ‘Rhine’ which is a river that runs along the border between Germany and France. The “just raked steamers” seem to be peacetime equivalents of the raking of gunfire, and one also senses echoes of the “empire” of Imperial Japan when the poet compares the steamers opening to the “empire of faces raised toward // a hiss from the sky” as they look at the “…flash that quenched astonished / cries.” Similarly, in the poem, “Currying a Gelding,” the quotidian scene is the “Far Hills Stables” where a riding instructor is grooming a horse and apologizes to the rider (who is the speaker in this poem) for the gelding who has tossed her. This poem references the Hungarian Uprising (October-November of 1956) against Soviet oppression, and the riding instructor is a Hungarian Freedom Fighter. A conversation ensues where the riding instructor reveals his past in Budapest: “…All I know / is horses // and how to kill.” And there we have it, the fractured self within a world where “…fantasy’s Oprah-rated,” to borrow words from the first sonnet (see “FUBAR’d”) and reality is a complex mixture of the pull and tug between persistence and vulnerability, between going through the motions of life and engaging with the oppressive weight of memory.

There are other marvelous poems in this section that have the flavor of memoir including “Understory” which is a snapshot of the impact of the speaker’s moment of witness, the realization that “voices hurtled” and “spoke my language made ugly,” followed by a sensation that “The air split open / from the slash of words / I turned to face.” Here we have personal disclosure of what it feels like to open consciousness to war realities. Similarly, we see in “Reading the Dark in the Dark” the graphic violence the speaker witnesses when reading about “…silhouettes / burned into Hiroshima’s walls,” and seeing a face “cheek smeary with eye-melt.” These horrors awaken the understanding that the darkness of not knowing resides in all of us “unless,” as the poet writes, “I keep reading it // to draw it toward light.” Here we can make an association with an earlier poem, “Dark of the Moon,” where Rumi is quoted: “…Go to the roof / and sing. Sing loud.” J.C. Todd’s poems “sing loud” and draw reality “toward light.”

It seems appropriate to conclude the review with a poem from the final section of Beyond Repair, titled “What’s Left.” In this poem, Todd refers to the writer “Olga T” who is Polish novelist Olga Tokarczuk, a Nobel laureate and activist. Todd writes when “Olga T’s” translations were published, “…she received a letter from Toronto,” whose writer indicated, “‘I think I am / your cousin.”’ It became apparent that people were hungry for information that would help them put together pieces of their past. But how does one piece together records destroyed in bombings? How does one reconcile the “racket and ruin” of the triage doctor, veterans with PTSD, citizens of Hama, Olga T’s characters, and all of those torn asunder by war? J. C. Todd writes about what is left, “… —a gap where half-told tales / might become a lineage.” Perhaps Beyond Repair is an entry into the gap, one that attempts to fashion a “lineage” of essential understanding through the process of paying attention to cruelty and inhumanity, of validating the unspeakable so that even if war creates situations beyond repair, an awakening of consciousness, and perhaps a new paradigm of interdependence, might emerge.

In our dream band, on timpani:

MC Catanese currently serves as a Community Teaching Assistant within the University of Pennsylvania’s continuous on-line program in Modern and Contemporary American Poetry. She has an undergraduate degree in Fine Arts/Music and a Master’s Degree from The Program for Administrators at Rider University. She was an Administrator for the Westminster Conservatory of Music in Princeton, New Jersey, before devoting extensive energies to making visual art and studying poetry.